Types of POTS

The classifications for POTS, autonomic nervous system conditions and syncope have been evolving over recent years as more is learned about orthostatic conditions like POTS and OH/NMH.

We will use the classifications that make it easier to understand the differences in symptoms and treatment, when it is known or understood.1,2

POTS is a heterogeneous condition and population. That means that people who have it all meet the basic criteria to be diagnosed with POTS and they have similar orthostatic symptoms but there are other ways they are very different. It developed after different triggers, which could mean the cause is different. Not everyone has the same test results. Not everyone responds the same to the management or the medications.

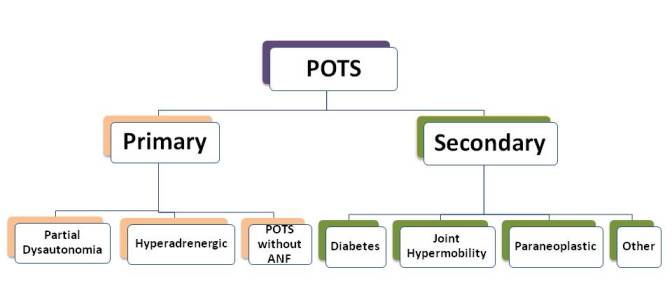

POTS can be divided into 2 different groups based on whether it has developed by itself (primary) or whether there is another medical condition that is known to cause autonomic nervous system failure, like POTS (secondary).

There is one subtype that can be identified by lab test results, hyperadrenergic POTS. There is a limited amount of information about that group.

So far, researchers like Dr. Stewart, have taken the information about the differences in test results, what started the condition or other differences to come up with a way to separate the information into "types" or "subtypes" but the information is more useful for research right now. It doesn't have enough information to help tell who will respond best to the different medications.

- Primary POTS

- Hyperadrenergic POTS or β-hypersensitivity

- Secondary POTS

- POTS with Deconditioning

There are 2 groups of 'primary' POTS.

POTS - Partial Dysautonomia

This considered to be a 'partial autonomic nervous system dysfunction' (or autonomic dysfunction).1,6 This is the form that affects most young people. It has other symptoms that are related to the dysfunction of the autonomic system (dysautonomia): problem with temperature regulation, sweat,

It is also believed that it is possible to have POTS without having any autonomic dysfunction.

The problem and how it affects standing up: It is a mild form of damage to the peripheral nerves (which is also called peripheral neuropathy). Because of the damage to the nerves to the blood vessels in the legs, arms, and the abdomen (GI - stomach/intestines), the blood vessels do not get narrower (constrict) when the person stands up. This means they hold more blood in the legs, lower arms and abdomen when the person stands up. This is referred to as "pooling" of blood. The body tries to compensate for the blood pooling by increasing the heart rate.

Who Gets Primary POTS: This form of POTS affects females more than males, 5:1. This is the type of POTS people get after an event like acute febrile illness (presumed to be viral), after pregnancy, surgery, sepsis, or trauma. Some studies have documented test results (ganglionic antibody) that indicate some of the patients with this form of POTS have an autoimmune disorder.3

Patients with this subtype often describe a more gradual start to their symptoms with more symptoms developing over time, as compared to a more abrupt onset described by those with Primary POTS.

In the Mayo experience, It is present in about 30% of the people with POTS.3 Some articles indicate that patients with hyperadrenergic POTS often report more significant tremor, anxiety, and cold sweaty extremities when they stand up.1,7 These are symptoms that are thought to be due to a higher level of epinephrine or norepinephrine (NE). In the analysis of the patient seen at Mayo, they did not find that the patients with the elevated NE did not have more of these symptoms.3

Other differences:

• Many people with this type often have orthostatic high blood pressure (hypertension) when they have orthostatic tachycardia (fast heart rate).6

• Over

half of these patients have migraine

headaches.

• Some people notice an

increase in urinary output after

standing up for only a short period of

time.

• There is often a strong family history.

• Some of the patients have a single point mutation that affects the reuptake transporter protein that recycles norepinephrine.

Lab results: They have a higher norepinephrine (NE) level when they stand up (over 600 pg/mL).

People with increased NE levels when standing up tend to have a better response to beta-blocker treatment than people who have a lower amount of NE (<600 pg/mL).3

Other medications may also be more effective. See Management of Hyperadrenergic POTS.

Fluid intake and high salt may not be appropriate for people with the hyperadrenergic form.1

This is often referred to a condition being "secondary". This means that there is another medical condition present and the POTS has developed as a result of the health problem or damage from the main medical condition. This form of POTS is thought to be different than the primary form. It is believed that there is loss of peripheral autonomic nerves or the peripheral nerves that go to the blood vessels do not respond properly. However, the autonomic nerves that go to the heart still work ok.1

Diabetes mellitus is a common cause of secondary POTS. Other medical conditions that also get POTS are amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, alcoholism, lupus, Sjögren syndrome, chemotherapy, vitamin deficiencies (vitamin B12 and folate), and heavy metal poisoning.1,2 Another associated condition is Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (JHS). 2

POTS may also found in people with the "Paraneoplastic Syndrome". This means they have a cancer like an adenocarcinoma of the lung, breast, ovary or pancreas.1 The POTS usually improves when the cancer has been treated.

Managing Secondary POTS: This type of POTS is managed much the same as the other Orthostatic Intolerance (OI) conditions. However, it may get worse if the main condition gets worse. Also, the management needs to be watched more closely because there is another medical condition present and possibly other medications. This would especially relate to the fluids and salt.

It is known that people with POTS do not do well with exercise. It is one of the symptoms that brings them to the physician. It is part of the symptom-list for POTS.

Deconditioning is often present, especially in people with conditions with prominent fatigue and where there has been prolonged bedrest, such as POTS, fibromyalgia type symptoms6 and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS).

One

For more information, check out the pages on Deconditioning?, Prolonged Bedrest, and Prolonged Bedrest & OI.

![]() Authors's Note: We will explore more of the information on Deconditioning and POTS, how to tell the difference and what needs to be done to recover. Follow us on Twitter or Facebook to be alerted when more is posted.

Authors's Note: We will explore more of the information on Deconditioning and POTS, how to tell the difference and what needs to be done to recover. Follow us on Twitter or Facebook to be alerted when more is posted.

References

- Grubb BP. Postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation. 2008;117:2814–2817. Abstract. Article PDF.

- Medow MS, Stewart JM, Sanyal S, Mumtaz A, Stca D and Frishman WH. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Orthostatic Hypotension and Vasovagal Syncope. Cardiology in Review 2008;16(1):4-20. Abstract

- Thieben MJ, Sandroni P, Sletten DM, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: The Mayo Clinic experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:308–313. Abstract.

- Stewart JM. Chronic orthostatic intolerance and the postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Pediatr. 2004;145:725–730. Article PDF

- Stewart JM, Medow MS, Alejos JC. Orthostatic Intolerance.2011. Medscape article.

- Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner and Shen W. Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS). J Cardopvasc Electrophysiology 2009; 20:352-358. Abstract. Article PDF

- Jordan J, Shannon JR, Diedrich A, Black BK, Robertson D: Increased sympathetic activation in idiopathic orthostatic intolerance: Role of systemic adrenoreceptor sensitivity. Hypertension 2002;39:173- 178. Abstract. Article PDF.

- Joyner Michael J, Masuki Shizue. POTS versus deconditioning: the same or different? Clin Auton Res. 2008 Dec;18(6):300-7. Epub 2008 Aug 12. Abstract.

- Tank J, Baevsky RM, Funtova II, Diedrich A, Slepchenkova IN, Jordan J Orthostatic heart rate responses after prolonged space flights. Clin Auton Res. 2011 Apr;21(2):121-4. Epub 2010 Dec 25. Abstract

- Johnson JN, Mack KJ, Kuntz NL, Brands CK, Porter CJ and Fischer PR. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: A Clinical Review. Pediatr Neuro 2010; 42:77-85. Abstract.

- Grubb BP, Karabin B. Cardiology patient page. Postural tachycardia syndrome: Perspectives for patients. Circulation. 2008;118:e61–e62. Abstract. Article PDF.

- Burkhardt BE, Pianosi PT, Brands CK, Porter CJ, Weaver AL, Fischer PR. Heart rate response to exercise in adolescents with autonomic dysfunction. Clin Autonom Res. 2007;17:266

Author: Kay E. Jewell, MD

Page Last Updated: June 22, 2012